So there had to be a structure, driven by, or reflecting, the extramusical narrative. Which is a biography of a life’s worth of experiences.

So how do you tell a life story in music?

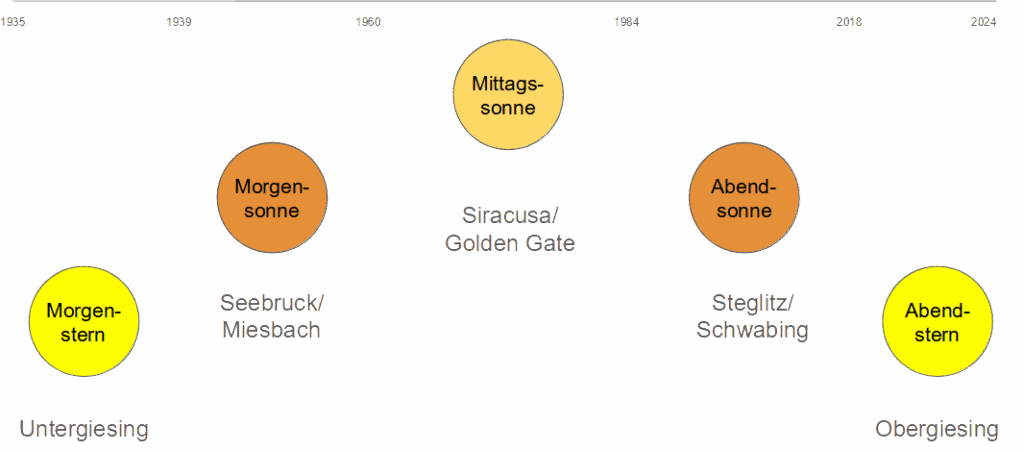

Celestial Bodies

Rather than a formal biography, I opted for individual snapshots. Short stories, or individual scenes, that reflect this biography. And which are somehow structured biographically.

Reflecting this over the course of a day, this would start with the morning star, end with the evening star, and has the sun moving over the sky in between. And with that, we already had our structure:

Geographical Biography

Unless you’re Immanuel Kant, the places you’ve been can represent a geographical map of your life. Especially if, like in the case of Prof. Max Straschill, it starts and ends in almost the same place.

Life started in Untergiesing, and life ended in Obergiesing, the historical worker (and football) districts of München (Munich). Which could map Giesing (both parts) to the two stars at the beginning and end.

Fill that with the childhood spent in Kinderlandverschickung during World War II, a young adulthood spent in various places, among them Syracusa (Sicily), San Francisco and the country home in Riedering, and a later adulthood anchored in Berlin-Steglitz (work) and München-Schwabing (life), and we have mapped the celestial bodies to places on earth, and by proxy to places in time as well.

Scenes – and a Narrative Arc

If this was a classical opera, we would start with an overture. I decided against it. Rather than starting with an abstract, there shouldn’t be any spoliers – rather during the last section, there should be a reflection, a summary.

And this is what Sapientia Salomonis, the only title in Abendstern, is. Opting for the queen of instruments (aka pipe organ) as the preferred instrumentation with the king of instruments (the piano) being a second choice, this was an easy choice.

At the other end of the spectrum, the music starts with a tongue-in-cheek statement, exemplified by the title, Erat Lausbub. While I was pretty clear that I wanted ensembles (rather than solo performances) for most of the album, Morgenstern starts as a solo as well: I had thought about various options, including alto saxophone, french horn and electric bass guitar, but also for sourcing reasons, settled for classical guitar. Classical instrumentation opens the arc, classical instrumentation closes it.

For the next three sections (indicated by the sun moving over the sky through the course of a day), I had very early thought about small, mostly acoustic or semi-acoustic instruments. I love brass, and Morgensonne is situated in the Bavarian countryside – so it’s trombone, tuba and electric guitar.

For Abendsonne (and the setting of full professor and whatnot), a small, classical-seeming lineup appeared sensible: With clarinet, cello and grand piano, there is a setup that is very flexible, able to cover grounds between old chamber music and outrageously modern stuff. And finally, for the young adult? Rock ’n‘ roll I’d say, so two electric guitars, electric bass guitar and drumkit it was.

Individual Parts – and Sizes

With the first and last section (the stars) covering about five years each, the rest of the almost 90 years are covered by the suns, for more than 20 years for each. So there’s more to tell for them, and more space required.

In the end, each sun got three individual tracks, aiming for a playing time of close to 15 minutes, with the stars together contributing another 10 minutes together – most probably too long for a single vinyl LP, but still, a good duration for a somewhat complex piece of music.